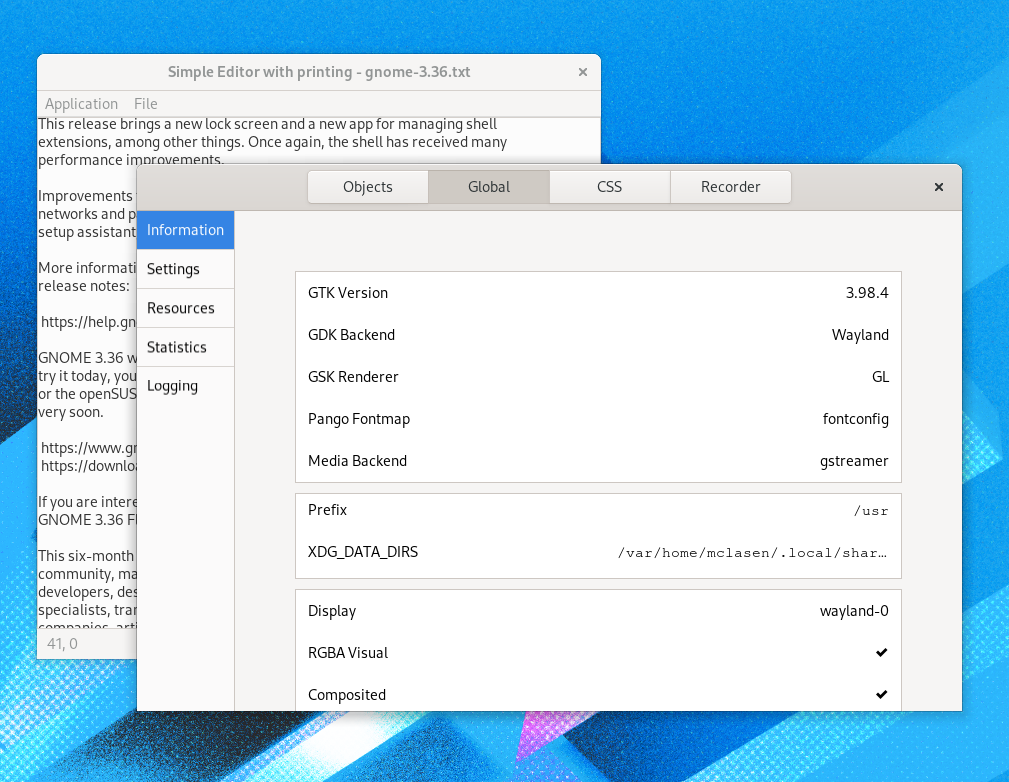

The previous post introduced the overall list view framework that was introduced in the 3.98.5 release, and showed some examples. In this post, we’ll dive deeper into some technical areas, and look at some related topics.

Trees

One important feature of GtkTreeView is that it can display trees. That is what it is named for, after all. GtkListView puts the emphasis on plain lists, and makes handling those easier. In particular the GListModel api is much simpler than GtkTreeModel—which is why there have been comparatively few custom tree model implementations, but GTK 4 already has a whole zoo of list models.

But we still need to display trees, sometimes. There are some complexities around this, but we’ve figured out a way to do it.

Models

The first ingredient that we need is a model. Since GListModel represents a linear list of items, we have to work a bit harder to make it handle trees.

GtkTreeListModel does this by adding a way to expand items, by creating new child list models on demand. The items in a GtkTreeListModel are instances of GtkTreeListRow which wrap the actual items in your model, and there are functions such as gtk_tree_list_row_get_children() to get the items of the child model and gtk_tree_list_row_get_item() to get the original item. GtkTreeListRow has an :expanded property that is used to keep track of whether the children are currently shows or not.

At the core of a tree list model is the GtkTreeListModelCreateModelFunc which takes an item from your list and returns a new list model containing items of the same type that should be the children of the given item in the tree.

Here is an example for a tree list model of GSettings objects. The function enumerates the child settings of a given GSettings object, and returns a new list model for them:

static GListModel *

create_settings_model (gpointer item,

gpointer unused)

{

GSettings *settings = item;

char **schemas;

GListStore *result;

guint i;

schemas = g_settings_list_children (settings);

if (schemas == NULL || schemas[0] == NULL)

{

g_free (schemas);

return NULL;

}

result = g_list_store_new (G_TYPE_SETTINGS);

for (i = 0; schemas[i] != NULL; i++)

{

GSettings *child = g_settings_get_child (settings, schemas[i]);

g_list_store_append (result, child);

g_object_unref (child);

}

g_strfreev (schemas);

return G_LIST_MODEL (result);

}

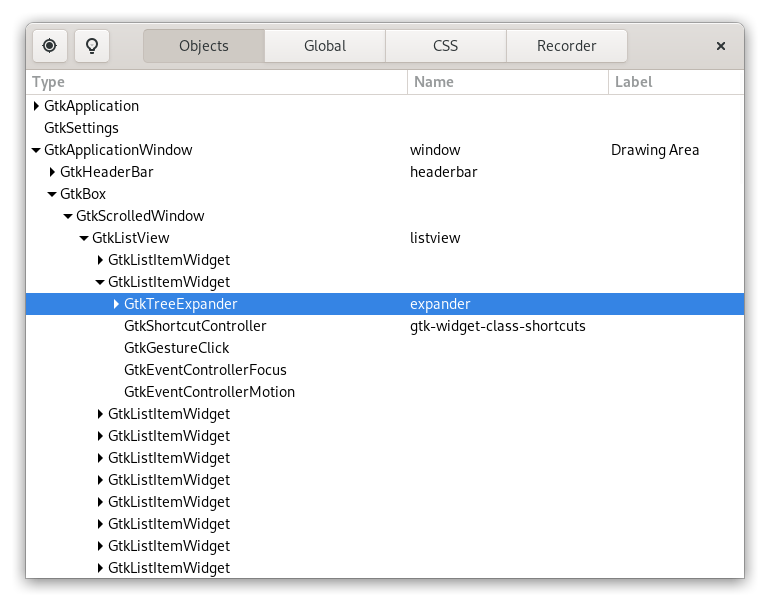

Expanders

The next ingredient that we need is a widget that displays the expander arrow that users can click to control the :expanded property. This is provided by the GtkTreeExpander widget. Just as the GtkTreeListRow items wrap the underlying items in your model, you use GtkTreeExpander widgets to wrap the widgets used to display your items.

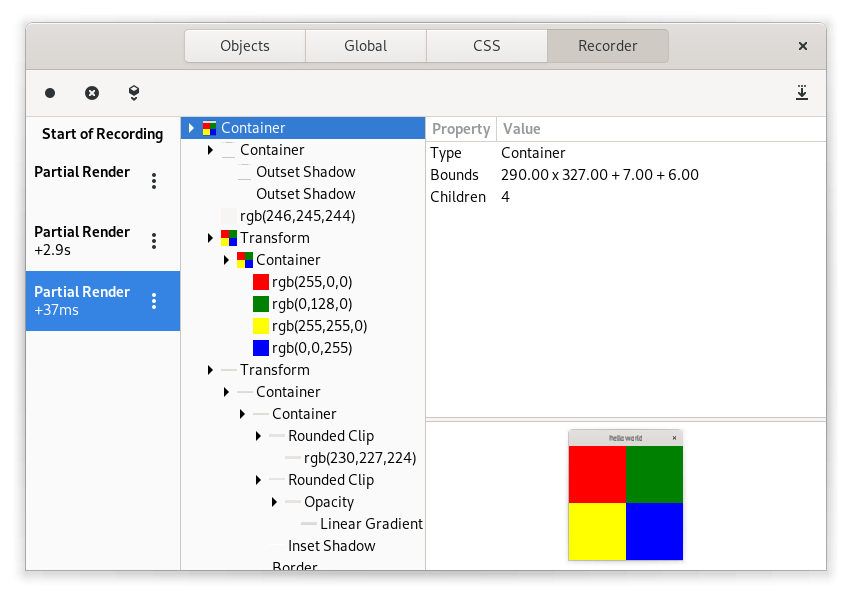

Here is how the tree expanders look in action, for our GSettings example:

The full example can be found here.

Sorting

One last topic to touch on before we leave trees is sorting. Lists often have more than one way of being sorted: a-z, z-a, ignoring case, etc, etc. Column views support this by letting you associate sorters with columns, which the user can then activate by clicking on the column headers. The API for this is

gtk_column_view_column_set_sorter (column, sorter)

When sorting trees, you typically want the sort order to apply to the items at a given level in the tree, but not across levels, since that would scramble the tree structure. GTK supports this with the GtkTreeListRowSorter, which wraps an existing sorter and makes it respect the tree structure:

sorter = gtk_column_view_get_sorter (view);

tree_sorter = gtk_tree_list_row_sorter_new (sorter);

sort_model = gtk_sort_list_model_new (tree_model,

tree_sorter);

gtk_column_view_set_model (view, sort_model);

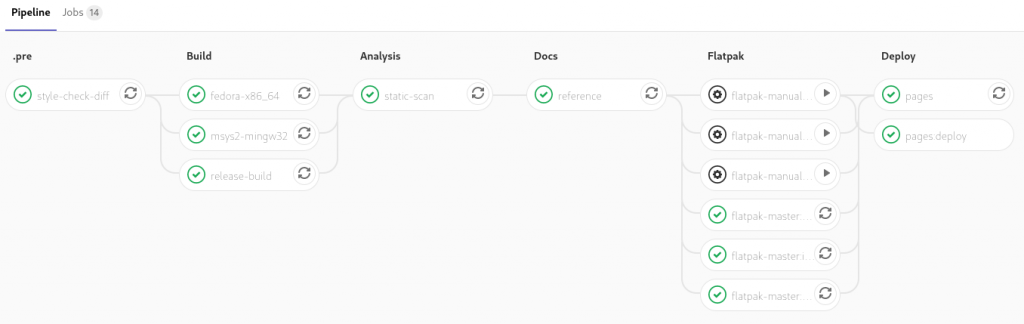

In conclusion, trees have been de-emphasized a bit in the new list widgets, and they add quite a bit of complication to the machinery, but they are fully supported, in list views as well as in column views:

Combo boxes

Combo boxes

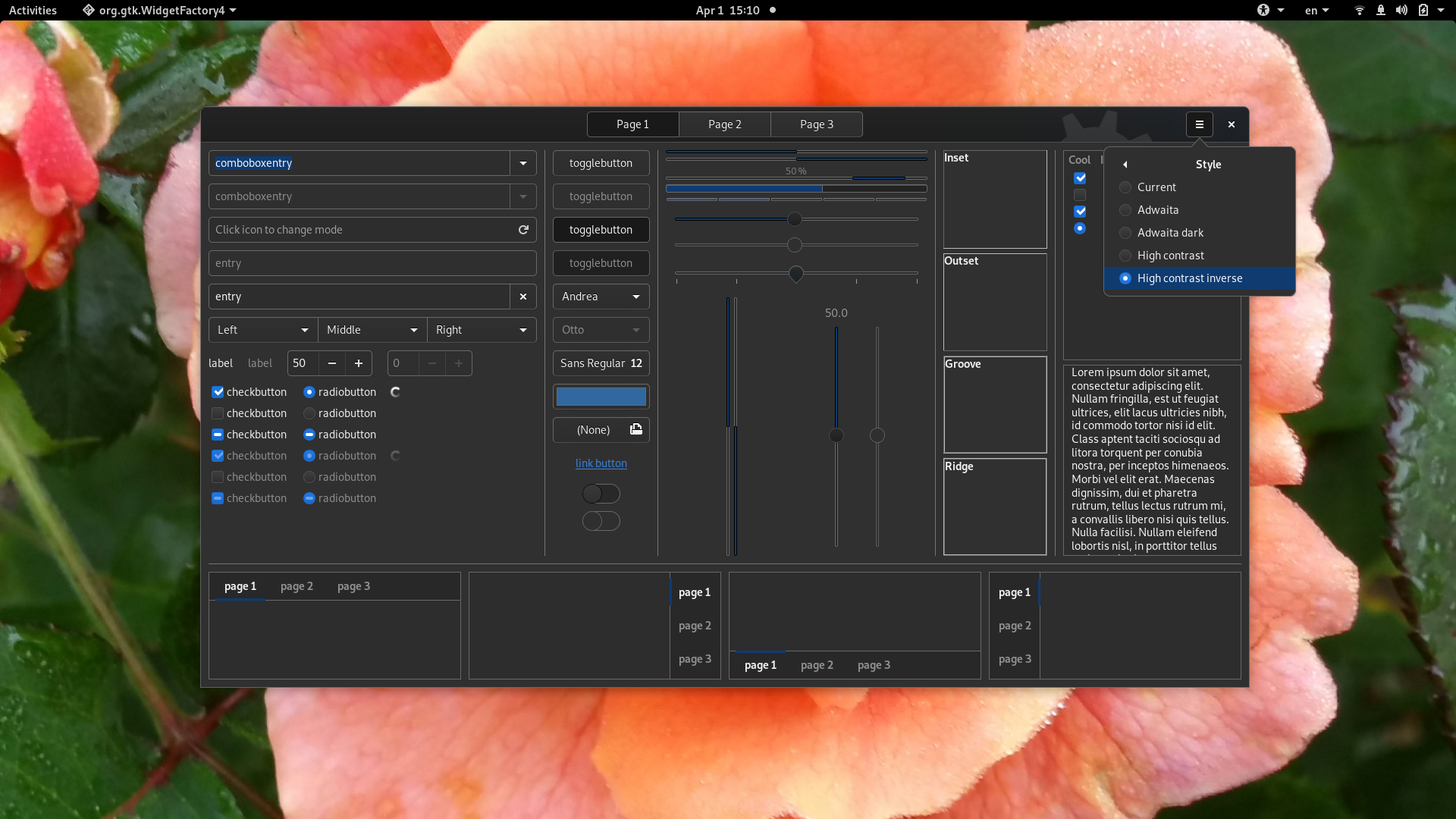

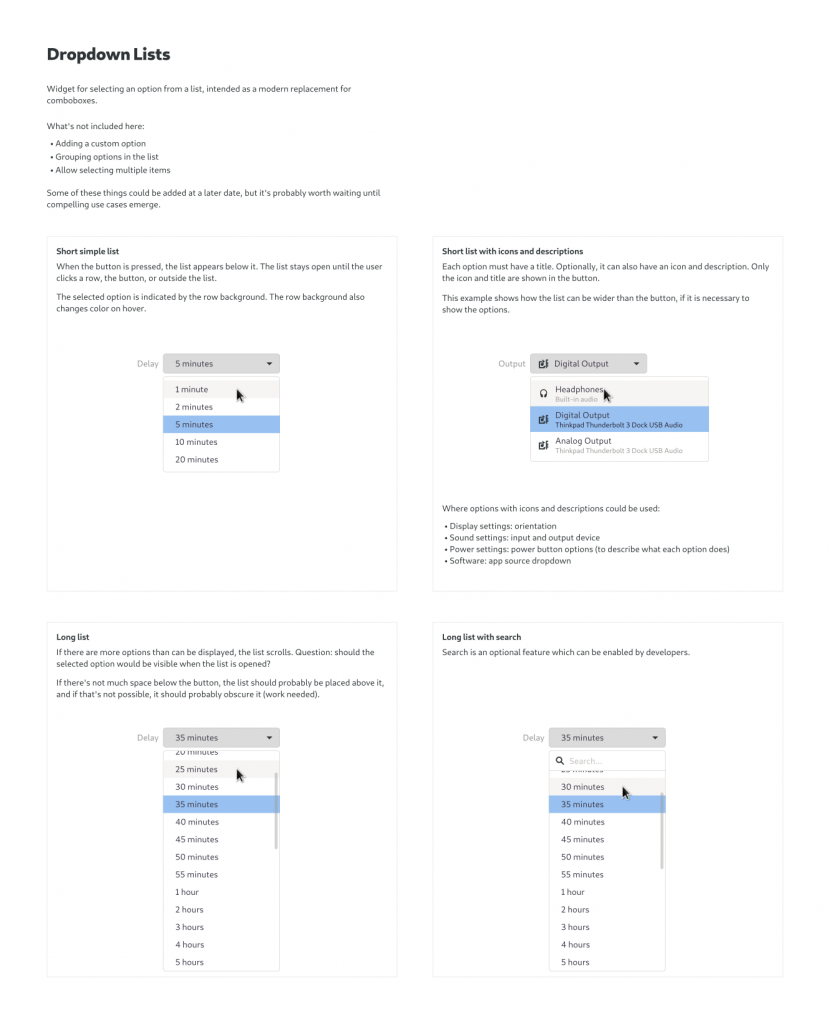

One of the more problematic areas where cell renderers are used is our single-selection control: GtkComboBox. This was never a great fit, in particular in combination with nested menus. So, we were eager to try the new list view machinery on a replacement for GtkComboBox.

From the design side, there has also been a longstanding wishlist item to do better for combo boxes, as can be seen in this mockup from 2015:

Five years later, we finally have a replacement widget. It is called GtkDropDown. The API of the new widget is as minimal as possible, almost all the work is done by list model and item factory machinery. Basically, you create a dropdown with gtk_drop_down_new(), then you give it a factory and a model, and you are done.

Five years later, we finally have a replacement widget. It is called GtkDropDown. The API of the new widget is as minimal as possible, almost all the work is done by list model and item factory machinery. Basically, you create a dropdown with gtk_drop_down_new(), then you give it a factory and a model, and you are done.

Since most choices consist of simple strings, there is a convenience method that creates the model and factory for you, from a string array:

const char * const times[] = {

"1 minute",

"2 minutes",

"5 minutes",

"20 minutes",

NULL

};

button = drop_down_new ();

gtk_drop_down_set_from_strings (GTK_DROP_DOWN (button), times);

This convenience API is very similar to GtkComboBoxText, and the GtkBuilder support is also very similar. You can specify a list of strings in the ui file like this:

<object class="GtkDropDown">

<items>

<item translatable="yes">Factory</item>

<item translatable="yes">Home</item>

<item translatable="yes">Subway</item>

</items>

</object>

Here are a few GtkDropDowns in action:

Summary

To stress this point again: all of this is brandnew API, and we’d love to hear your feedback on what works well, what doesn’t, and what is missing.

Keeping control

Keeping control