(This is the fifth part of a series about custom widgets in GTK 4. Part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4).

Activate all the things

Many things in GTK can be activated: buttons, check boxes, switches, menu items, and so on. Often, the same task can be achieved in multiple ways, for example copying the selection to the clipboard is available both via the Control-C shortcut and an item in the context menu.

Inside GTK, there are many ways things can proceed: a signal may be emitted (::activate, or ::mnemonic-activate, or a keybinding signal), a callback may be called, or a GAction may be activated. None of this is entirely new in GTK 4, but we are moving towards using GActions as the primary mechanism for connecting actions.

Actions

Actions can appear in various forms in a GTK application.

First, there are global application actions, added to GtkApplication or GtkApplicationWindow (both of these implement the GActionGroup interface). This is where actions first appeared in GTK 3, mainly for the purpose of exporting them on the session bus for use with the app menu.

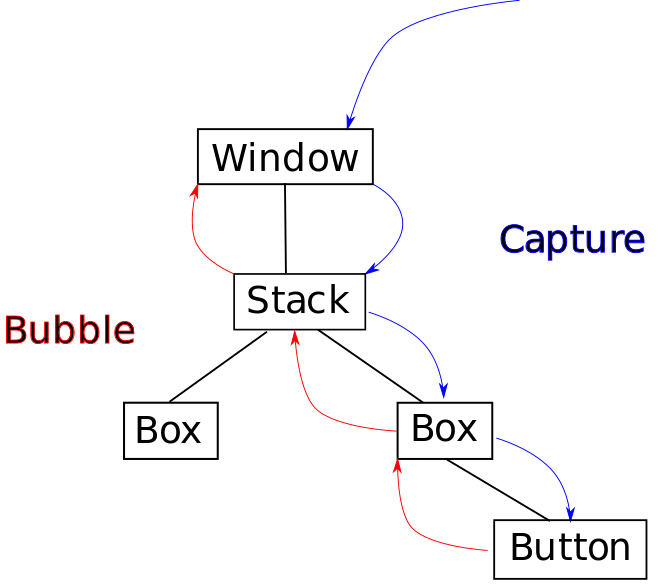

We also allow to associate actions with widgets by calling gtk_widget_insert_action_group(). Actions that are added in this way are only considered for activation when it originates in below the widget in the hierarchy.

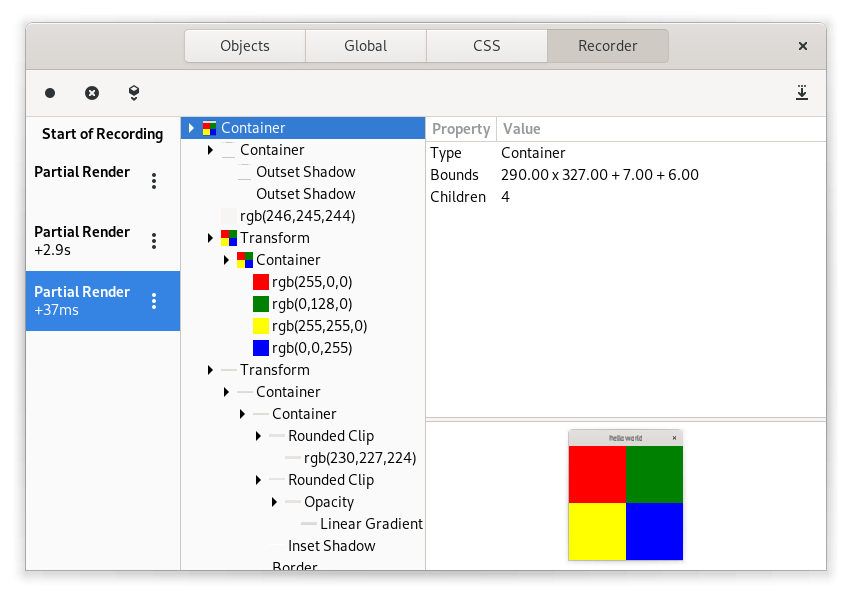

A new way to create actions in GTK 4 is to declare actions in the class_init function, via gtk_widget_class_install_action(), similar to how properties are declared with g_object_class_install_property(). Actions created in this way are available for every instance of the widget.

Here is an example from GtkColorSwatch:

gtk_widget_class_install_action (widget_class,

"color.customize", "(dddd)",

customize_color);

The customize_color function is called when the color.customize action is activated. As you can see, actions can declare that they expect parameters. This is using GVariant syntax; you need to provide four double values.

A convenient shorthand allows you to create a stateful action to set a property of your widget class:

gtk_widget_class_install_property_action (widget_class,

"misc.toggle-visibility",

"visibility");

This declares an action with the name misc.toggle-visibility, which toggles the value of the boolean visibility property.

Actionables and Menus

Declaring actions only goes so far, you also need to connect your actions to the UI in some form. For widgets like buttons or switches that implement the actionable interface, this is as easy as setting the action-name property:

gtk_actionable_set_action_name (GTK_ACTIONABLE (button),

"misc.toggle-visibility");

Of course, you can also do this in a ui file.

If you want to activate your actions from a menu, you will likely use a menu model that is constructed from XML, such as this:

<menu id="menu">

<section>

<item>

<attribute name="label">Show text</attribute>

<attribute name="action">misc.toggle-visibility</attribute>

</item>

</section>

</menu>

In GTK 3, you would connect to the ::populate-popup signal to add items to the context menus of labels or entries. In GTK 4, this is done by adding a menu model to the widget:

gtk_entry_set_extra_menu (entry, menu_model);

Going deeper

To learn more about actions in GTK 4, you can read the action overview in the GTK documentation.