In my last post on this topic, I explained the history of SVG in GTK, and how I tricked myself into working on an SVG renderer in 2025.

Now we are in 2026, and on the verge of the GTK 4.22 release. A good time to review how far we’ve come.

Testsuites

While working on this over the last year, I was constantly looking for good tests to check my renderer against.

Eventually, I found the resvg testsuite, which has broad coverage and is refreshingly easy to work with. In my unscientific self-evaluation, GtkSvg passes 1250 of the 1616 tests in this testsuite now, which puts GTK one tier below where the web browsers are. It would be nice to catch up with them, but that will require closing some gaps in our rendering infrastructure to support more complex filters.

The resvg testsuite only covers static SVG.

Another testsuite that I’ve used a lot is the much older SVG 1.1 testsuite, which covers SVG animation. GtkSvg passes most of these tests as well, which I am happy about — animation was one of my motivations when going into this work.

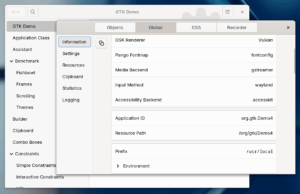

Benchmarks

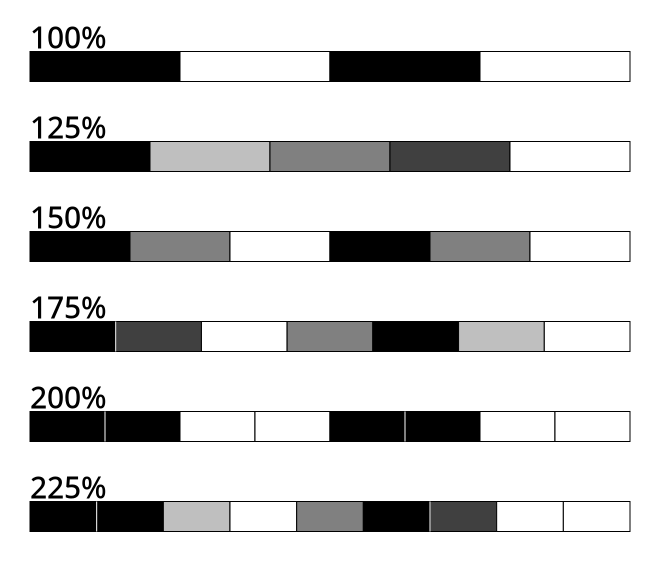

But doing a perfect job of rendering complex SVG doesn’t do us much good if it slows GTK applications down too much. Recently, we’ve started to look at the performance implications of SVG rendering.

We have a ‘scrolling wall of icons’ benchmark in our gtk4-demo app, which naturally is good place to test the performance impact of icon rendering changes. When switching it over to GtkSvg, it initially dropped from 60fps to around 40 on my laptop. We’ve since done some optimizations and regained most of the lost fps.

The performance impact on typical applications will be much smaller, since they don’t usually present walls of icons in their UI.

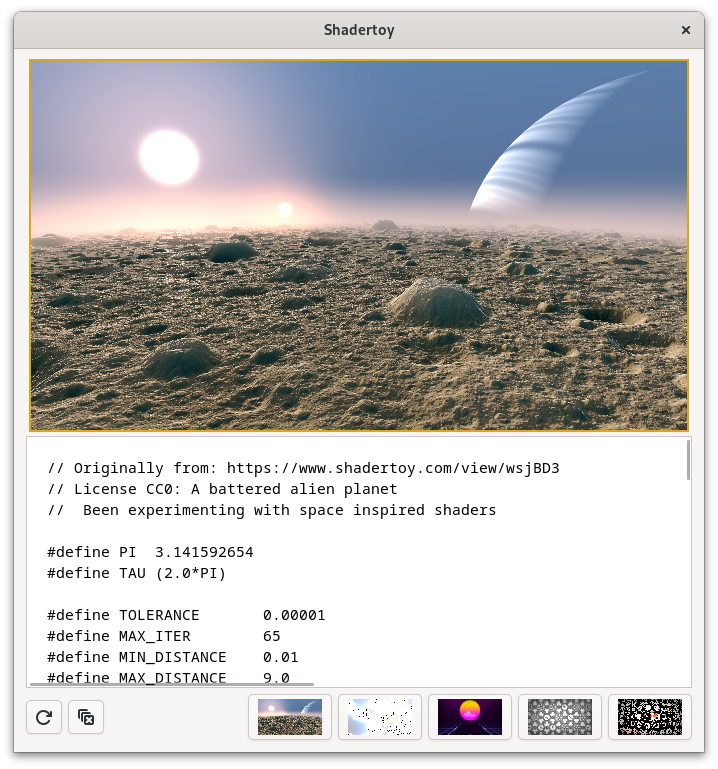

Stressing our rendering infrastructure with some more demanding content was another motivation when I started to work on SVG, so I think I can declare success here.

Content Creators

The new SVG renderer needs new SVGs to take advantage of the new capabilities. Thankfully, Jakub Steiner has been hard at work to update many of the symbolic icons in GNOME.

Others are exploring what we can do with the animation capabilities of the new renderer. Expect these things to start showing up in apps over the next cycle.

Others are exploring what we can do with the animation capabilities of the new renderer. Expect these things to start showing up in apps over the next cycle.

Future work

Feature-wise, GtkSvg is more than good enough for all our icon rendering needs, so making it cover more obscure SVG features may not be big priority in the short term.

GtkSvg will be available in GTK 4.22, but we will not use it for every SVG icon yet — we still have a much simpler symbolic icon parser which is used for icons that are looked up by icon name from an icontheme. Switching over to using GtkSvg for everything is on the agenda for the next development cycle, after we’ve convinced ourselves that we can do this without adverse effects on performance or resource consumption of apps.

Ongoing improvements of our rendering infrastructure will help ensure that that is the case.

Where you can help

One of the most useful contributions is feedback on what does or doesn’t work, so please: try out GtkSvg, and tell us if you find SVGs that are rendered badly or with poor performance!

Update: GtkSvg is an unsandboxed, in-process SVG parser written in C, so we don’t recommend using it for untrusted content — it is meant for trusted content such as icons, logos and other application resources. If you want to load a random SVG of unknown providence, please use a proper image loading framework like glycin (but still, tell us if you find SVGs that crash GtkSvg).

Of course, contributions to GtkSvg itself are more than welcome too. Here is a list of possible things to work on.

If you are interested in working on an application, the simple icon editor that ships with GTK really needs to be moved to its own project and under separate maintainership. If that sounds appealing to you, please get in touch.

If you would like to support the GNOME foundation, who’s infrastructure and hosting GTK relies on, please donate.

❤️